Introduction and summary

Starting in 2022, the United States began a manufacturing renaissance, one defined by the transition to clean technology manufacturing and low-emission processes that will be necessary to stay competitive in the global economy. If the world is to secure a safe climate future, the manufacturing sector will be crucial in producing the technologies needed to mitigate emissions from the power and transportation sectors, and it must also decarbonize its own highly emissive processes. However, one critical element must not be overlooked: The manufacturing industry must be resilient against the rising threat of cyberattacks. Failing to meet the moment on either climate change or cybersecurity will pose threats to safety, critical infrastructure, national security, and the U.S. economy, as both emerging risks are bound to intensify.

The manufacturing sector—which includes everything from steel to electronics to cars—is the most targeted industry for cyberattacks and accounted for about one-quarter of incidents in 2024, both nationally and worldwide.1 This is in part because many industrial systems are decades old and were not built to be compatible with modern cybersecurity practices.2 The same legacy infrastructure is also a major obstacle to climate goals. The prevalence of old, typically fossil fuel facilities built before an awareness of their climate impact means that the manufacturing sector is highly emissive. Manufacturing is responsible for 20 percent of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions nationwide, with industry—which includes the manufacturing subsector—on track to be the highest emitting sector in the United States by 2035.3

Due in large part to the pro-manufacturing policies of the Biden administration, the United States was on track for a manufacturing boom, which had the potential to address both problems. Laws such as the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) of 2021 and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 helped push industry in a cleaner direction by providing incentives for companies to reduce their carbon emissions and produce clean technologies. In less than three years, quarterly investment in clean technology manufacturing more than tripled, with nearly 400 new facilities announced since the IRA passed.4 As money has already begun to flow for revamps, new facilities, and demonstration projects, manufacturers could use this influx of capital as an opportunity to strengthen cyber resilience and accelerate decarbonization at the same time.

Yet this moment of opportunity is under threat. Rather than building on the momentum of the past few years, the Trump administration and congressional Republicans passed the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which dismantled nearly all the policies that jump-started the manufacturing boom.5 The legislation gutted incentives to produce clean energy and manufacture and sell domestic clean vehicles, slashing demand for domestic supply chains and manufacturing of clean technologies. The administration also canceled $3.7 billion in funding to clean industrial demonstration projects, many of which assisted manufacturers in reducing their emissions by implementing new technologies.6 On cybersecurity, too, the administration has dissolved programs that support private companies, reduced the federal cyber workforce, and pulled back support for states.7 These actions leave an already vulnerable industry even more at risk and reduce the support many manufacturers needed to modernize and secure their facilities. The federal government is best suited to address these challenges, and the Trump administration’s reversal on federal leadership to address these challenges will have serious consequences for domestic industries, the workforce, and the economy.

Meanwhile, state policymakers can still take some steps to at least partially fill the gaps left by the federal government as policy debates play out in Washington. States should create financial incentives for companies to both decarbonize and implement cybersecurity best practices and create state- or regional-level initiatives for public-private information sharing, technical assistance, and recommendations for mitigation. Their actions could help reduce risks today and provide model policies for future federal leadership.

U.S. manufacturing at risk: The growth of cyber vulnerabilities

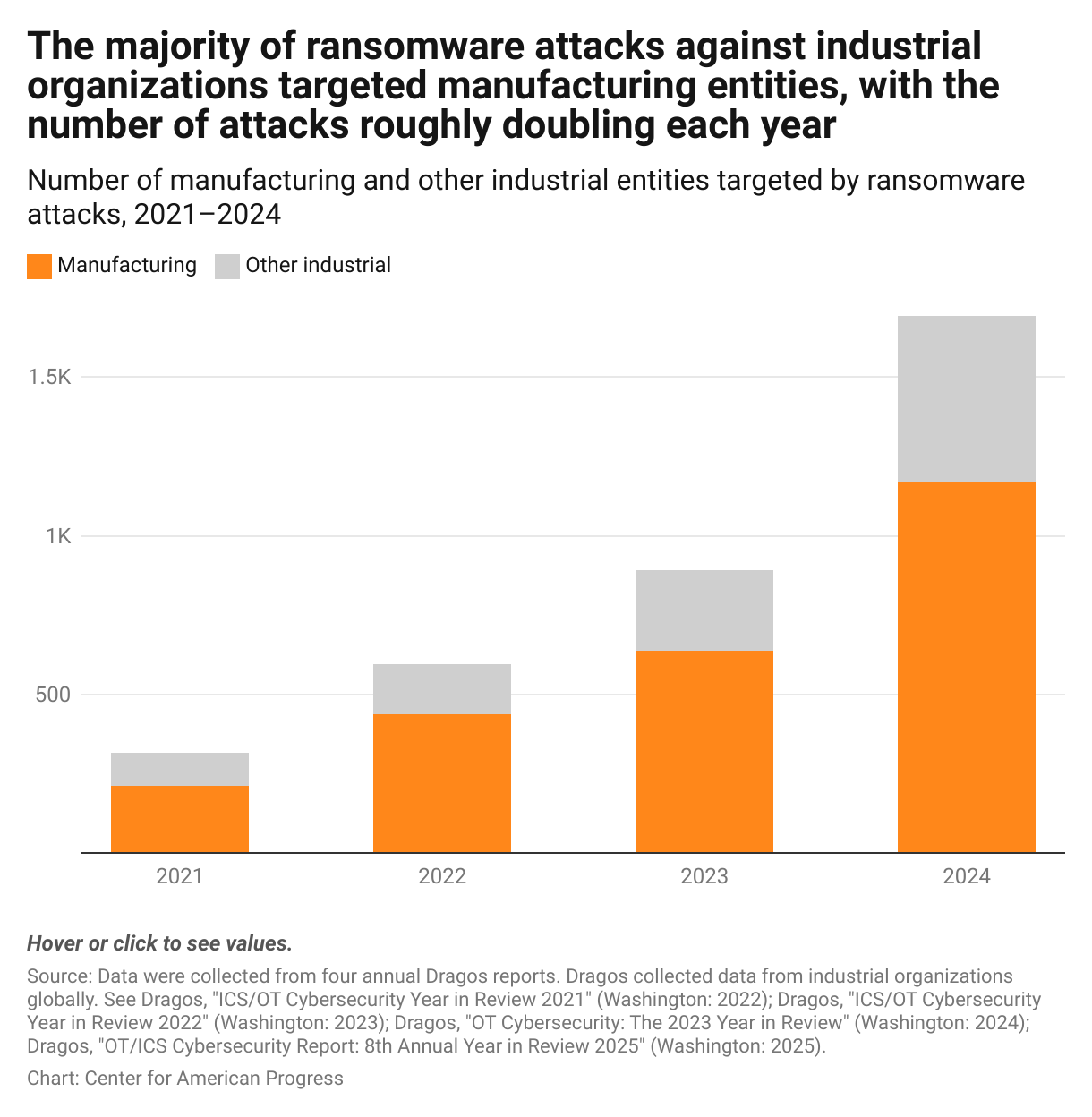

Manufacturing has become increasingly vulnerable to cyberattacks and has been the most targeted industry for four years in a row.8 Many of these attacks are motivated by the high-value payoffs of targeting facilities—whether access to valuable intellectual property and operational data or million-dollar ransom payments.9 In 2024, ransomware attacks against industrial organizations increased 87 percent over the previous year, with the majority—more than 1,000 attacks—directed at manufacturing.10 While these attacks are a global issue, North America faced more than the rest of the world combined.11 Other attacks, some backed by nation-states, are more interested in causing harm to economic and national security, potentially risking the safety of workers and the nation’s critical infrastructure.12

FIGURE 1

Manufacturing relies heavily on operational technology (OT), the hardware and software that manage physical processes and machinery, and industrial control systems (ICS), a subset of OT focused on controlling and automating industrial processes.13 Many OT systems are outdated, operating on legacy systems developed decades ago, long before the need for built-in security systems.14 Most of this legacy infrastructure is incompatible with modern security practices and is missing essential features such as secure authentication and encryption, making it an easy target.15 Forty-four percent of large organizations reported that their highest barrier to cyber resilience was securing legacy technology.16

The most staggering example of the risks of legacy systems was detected last year, when a Chinese cyber espionage campaign called Salt Typhoon launched an extremely widespread and damaging series of cyberattacks across the United States.17 The campaign targeted legacy systems throughout the telecommunications industry that were too old to implement strong cybersecurity practices, including encryption.18 The campaign went undetected for months and gained access to a large number of Americans’ communications—text messages, phone calls, and private data—including the private data of the 2024 presidential candidates and other U.S. elected officials.19 The breach affected critical industries, government systems, health care, and energy infrastructure, and it underscored the vulnerability of legacy systems in any industry.

Operational technology, particularly for heavy industry, is usually highly customized, meaning that security approaches need to be developed specifically for each operation—a process that can be both cost intensive and time intensive.20 Many security tools cannot be applied to OT or may require workarounds that are less effective in managing risks.21 And while cybersecurity for information technology (IT) is well established, OT has a lower level of cybersecurity maturity and not enough skilled workers to fill the growing demand.22 In addition to the difficulty of properly addressing these vulnerabilities, improvements often require shutting down production or redesigning processes, which can have high costs while affecting profits. For this reason, manufacturing facilities frequently underinvest in cyber resilience, especially smaller companies for which cost can be an even greater barrier.23

Yet as digitization has become essential to staying competitive, facilities have added new, internet-connected technologies through the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT), the digital connection to supply chain networks, automation, and machine learning. Manufacturers are digitizing at twice the rate of other businesses.24 This transition to smart manufacturing often means adapting legacy infrastructure that was never designed to be digitized. While these adaptations can increase efficiency and profit, the often haphazard combination of new and old systems can create vulnerable gaps in security coverage that are easily exploited.25 One of the first examples of this type of vulnerability was the 2015 attack on Ukraine’s power grid, in which Russian nation-state cyber actors gained remote access to the systems controlling circuit breakers and disrupted electricity for nearly 230,000 customers.26

Manufacturers have become more aware of the risks of cyberattacks in recent years, but many continue to be unprepared. In 2024, cybersecurity was ranked as one of the top five external risks to manufacturers for the first time, behind inflation and rising energy costs.27 However, only 45 percent of manufacturing companies state that they are well prepared for the convergence of OT and IT cybersecurity risks, and 13 percent of companies report being completely unprepared.28

The devastating costs of a cyberattack

In 2024, cyberattacks affected a range of manufacturers—from clothing and packaging to aerospace and automotive—causing widespread financial harm. According to an IBM analysis, the past two years have seen a shift from data breaches and reputational damage being the biggest concern, to wide-scale business disruption becoming a real possibility.29 In 2024, the average cost of a cyberattack in the industrial sector was $5.56 million, an $830,000 increase from 2023.30 Some incidents cost more than $200 million.31 For manufacturers affected by ransomware attacks—for which there were more than 850 incidents from 2018 to 2024—just the cost of downtime averaged $1.9 million per day.32 Most facilities lost an average of nearly 12 days to downtime, with a high of 129 days, and some ended up also paying the ransom demanded, which averaged another $10.7 million per incident.33 Nearly half of these attacks occurred in the United States, for a total of $8.27 billion in lost downtime costs.34

FIGURE 2

In addition to the costs of downtime, rebuilding machinery and cybersecurity systems, and investigations, public relations, and legal fees—each of which can cost millions of dollars—there are additional costs that are harder to measure. According to a Deloitte study, up to 90 percent of the total cost of a cyber incident is from intangible losses that may take years to resolve, such as the effects of a damaged reputation, loss of intellectual property, credit rating impacts, and increased insurance premiums.35 In a hypothetical scenario of a cyberattack on a U.S. technology manufacturer, Deloitte estimated a cost of $26 million for cybersecurity investigation and improvements, attorneys fees, and public relations, plus an additional $3.2 billion in intangible, “beneath the surface” costs over the course of five years.36

These staggering costs can easily force a business to shut down or declare bankruptcy, potentially resulting in hundreds of employees losing work.37 For businesses that stay afloat, the high costs of an attack are likely to trickle down to consumers. In 2024, 63 percent of organizations stated they would increase the cost of goods or services because of experiencing a data breach.38 Prices may also rise if the cyberattack severely affects the supply of a good, as was the case in 2021 when an attack on the Colonial Pipeline caused widespread fuel shortages, which led to increased gasoline prices.39

A successful cyberattack can create costs for not only the facility targeted but also the entire ecosystem to which it is connected. Companies that are dependent on the products of the targeted manufacturer may be affected by a pause in production. For example, a 2023 attack on the U.S. semiconductor equipment manufacturer MKS Instruments cost the company $200 million. Its customer, Applied Materials, lost an additional $250 million in revenue since the company was dependent on MKS for supplies.40 Pulling back even further, if there were to be widespread disruptions to facilities across an entire industry, there could be broad consequences for the U.S. economy or even national security concerns, depending on the products affected. For example, in May 2025, the United States’ largest steel manufacturer, Nucor, was affected by a cyberattack that forced it to shut down production at several facilities. Nucor is the primary supplier of rebar—steel bars used for building reinforcement, roads, and bridges—which means that disruption of production could have ripple effects throughout supply chains and lead to increased prices.41

Other entities digitally connected to a facility may be similarly affected by a cyberattack, including in the energy, logistics, and IT sectors. Vulnerabilities and disruptions for one part of a connected network can snowball into widespread security risks for all.42 This added complexity also means that vulnerabilities can be beyond the control of any single entity and often impossible to anticipate. A 2023 survey found that 54 percent of organizations reported having an insufficient understanding of the cyber vulnerabilities in their supply chain, and of the organizations that suffered a material incident in the previous year, 41 percent said it was caused by a third party.43

A 2023 survey found that 54 percent of organizations reported having an insufficient understanding of the cyber vulnerabilities in their supply chain, and of the organizations that suffered a material incident in the previous year, 41 percent said it was caused by a third party.

In addition to the financial costs of cyberattacks, the number of incidents that have caused physical consequences at manufacturing facilities has been doubling annually since 2019.44 Just a decade ago, a German steel mill was the target of one of the first known cyberattacks on an industrial facility that caused physical damage. The attackers gained control of the plant equipment, causing several areas to fail and leaving operators unable to properly shut down the blast furnace, which led to massive damage.45 Yet in 2023 alone, there were nearly 70 attacks that caused physical damage, impairing operations at more than 500 sites.46 The physical consequences included production and loading disruptions, as well as fires, explosions, and other accidents that put workers and possibly communities at risk. There have been several incidents where attackers have gained access to U.S. water treatment plants, with the potential of changing the amount of chemicals in the water and thus making it dangerous to drink.47 In 2017, a near-miss attack on a petrochemical plant in Saudi Arabia targeted the safety systems that were designed to prevent explosions and toxic leaks.48 The same systems that ended up compromised in the Saudi Arabian plant were, at the time, used in about 18,000 plants around the world, including nuclear and water treatment facilities.49 Had the attackers of the Saudi Arabian plant been successful, the public and environmental harm could have been catastrophic.

The convergence of climate impacts and cyberattacks

In addition to the digital vulnerabilities the manufacturing sector faces from cyberattacks, it is also increasingly at risk of climate disasters. The effects of such disasters can be similar to those of a cyberattack: power outages, destroyed equipment, and even devastating impacts on the environment and public health. For example, in 2017, there were more than 100 toxic releases in Houston due to Hurricane Harvey, and at least 365 tons of hazardous chemicals—including carcinogens—spilled into communities and waterways across Texas.50 Extreme weather disasters exponentially increase the risk of cyberattacks, as cybercriminals take advantage of companies made more vulnerable than normal by such events.51

Climate disasters can cause power outages that disable firewalls and other automated defenses or infrastructure damage that pushes primary servers offline, forcing employees to use unsecured backups or personal devices.52 In addition, employees have delayed response times due to the chaos created by a climate disaster.53 A recent study on the energy sector examined the compound effects of climate change impacts and cyberattacks and the possibility of malicious actors using an extreme weather event to disguise a cyberattack. Using the case study of a cyberattack during a heat wave, it found that a compound cyber-physical threat can exacerbate regional electricity disruptions by three times and exacerbate economywide losses by 10 times.54

Moving to resilience: Tackling cybersecurity as the United States decarbonizes manufacturing

Properly securing an industrial system requires consistent attention, upgrades, and investment, and for facilities operating with decades-old systems, the most effective choice may be to completely overhaul their operations in favor of newer models. For most companies, the high cost is the biggest barrier, even if the up-front expenses of securing their operations pale in comparison with the potential losses of a successful attack.

Over the past few years, the United States saw the beginning of a manufacturing renaissance led by clean investments, after nearly 50 years of decline.55 Companies invested more than $100 billion in clean technology manufacturing projects in the past two years, which was nearly four times the investment of the previous two years.56 There has been another $56 billion announced to decarbonize existing industrial facilities and processes.57 From January 2020 to January 2025, construction spending on manufacturing tripled.58 This boom was largely due to the investments and pro-manufacturing policies of the Biden administration, most notably the IIJA and the IRA.59 These laws incentivized hundreds of billions of dollars in private investment, primarily aimed at uplifting clean technology manufacturing and reducing carbon emissions from the highly emissive industrial sector. If this influx of capital had continued, it could have provided manufacturers with an opportunity to address the high cost barrier and improve their cyber resilience while they modernized their systems or to build more secure facilities from the ground up by taking advantage of federal investment opportunities.

However, the Trump administration and congressional Republicans’ One Big Beautiful Bill Act dismantled nearly all of the policies that jump-started the manufacturing boom.60 By gutting the incentives to produce clean energy and manufacture and sell domestic clean vehicles, the legislation will reduce demand for domestic supply chains and manufacturing of clean technologies. In addition, the administration canceled $3.7 billion in funding to demonstration projects, many of which assisted manufacturers in reducing their emissions by implementing new technologies.61 The companies that have already benefited from the historic investments of the past two years and plan to complete their projects have an opportunity to reimagine their systems to be cyber resilient and compatible with leading-edge technologies. But for the planned projects that will now be canceled, a unique opportunity for modernization has been thrown away. New ways of thinking are required to help companies overcome the high costs needed to modernize.

Read more

Cyberattacks are best prevented when cyber resilience is built into the initial design of industrial systems and processes. Security features that are added on later, rather than intrinsically built into system design, are less effective and more expensive.62 For the clean manufacturing transition, this presents a double-edged sword. On one hand, the many new facilities were designed for the modern, digital world, so they are better able to incorporate the most up-to-date security processes and to be upgraded as new strategies emerge. If companies develop these new systems with security in mind through cyber-informed engineering, they have an opportunity to create facilities that are truly of the future: decarbonized and cyber resilient.63 Since smaller companies frequently underinvest in cyber resilience for their facilities due to the cost of upgrades and downtime, retrofitting or building a new facility offers the perfect opportunity to address cyber vulnerabilities without also affecting production schedules.64

On the other hand, the companies that are investing in adapting their existing infrastructure are in for more of a challenge. For example, projects aiming to reduce their current emissions may implement energy-efficient technologies such as IIoT sensors that monitor energy usage and identify inefficiencies.65 This can lead to security gaps between legacy systems and digital adaptations that can leave facilities even more vulnerable.66 Companies must consider the added cybersecurity complexities in the initial design of these adaptations—and not as an afterthought. Doing so may require additional time and resources but could prevent higher costs down the line.

Facilities that are reducing emissions through electrification and connecting to the electricity grid must take similar precautions. Electrification is one of the most effective strategies to cut GHG emissions for several industries—particularly for light manufacturing industries such as textiles, vehicles, and food production, which do not require high temperatures.67 Yet connecting to the grid creates another vulnerability, as the grid itself has proved difficult to secure.68 As the grid modernizes from legacy, fossil fuel generation to digitally enabled clean energy, there is a chance to replace fragile systems with inherently more defensible ones.69 If done well, this will also benefit the industries connected to the grid.

The United States cannot afford to backtrack on cybersecurity or climate progress

At a minimum, it is essential that existing programs that address cybersecurity for manufacturing, the clean technology transition, and critical infrastructure security stay in place and fully staffed. Yet the first six months of the Trump administration have seen a weakening of all three across multiple agencies, despite claims of prioritizing national security, competitiveness, and economic growth.70

One of the Trump administration’s first moves was to dissolve the Cyber Safety Review Board (CSRB), a bipartisan, public-private initiative created to analyze major cyberattacks and provide recommendations.71 The board brought together government and industry leaders to identify lessons learned from incidents. It was in the middle of investigating Salt Typhoon, which may have been the worst telecommunications intrusion in U.S. history.72 The CSRB had not yet been able to determine the scope of the damage, and as recently as May 2025, U.S. officials said Salt Typhoon remains active in U.S. networks.73 The lessons that could be learned from this event—and future cyberattacks—are essential not only for telecommunications companies but also for any industry reliant on legacy systems for which similar intrusions could occur.

Shortly after dissolving the CSRB, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), which leads national efforts on cyber defense and resiliency, came under attack.74 Despite the fact that CISA was established during the first Trump presidency, Project 2025—the far-right road map intended for a conservative administration—suggested gutting the agency due to its work on election security in 2020.75 The Trump administration appears to be following this playbook and has already cut millions of dollars in CISA funding for two cybersecurity initiatives.76 After firing—and then being required to reinstate—CISA’s probationary employees, the White House suggested cutting more than 1,000 positions from the 3,700-person agency in its fiscal year 2026 budget proposal. Roughly 1,000 people have already left since Trump took office.77 The administration’s budget also proposes cutting $495 million from the agency.78 Such cuts are expected to affect every program in the agency.79

CISA works to coordinate the defense of critical infrastructure across government and industry, which includes the critical manufacturing sector. This subset of industry includes the manufacturing of primary metals, machinery, electrical equipment, and transportation equipment and is crucial to U.S. economic growth and national security.80 The agency helps manufacturing owners and operators manage risks and implement better practices in response to both cyber threats and physical threats such as natural disasters.81 However, the management of this critical infrastructure sector is done by CISA’s Stakeholder Engagement Division, for which the Trump administration’s budget proposes cutting 62 percent of funding.82 In addition to critical manufacturing, this division manages CISA’s relationships with several other private sector industries, including the chemical sector; emergency services sector; and nuclear reactors, materials, and waste sector.83 The National Risk Management Center at CISA also identifies the most significant risks in the 16 critical infrastructure sectors and promotes risk reduction. Yet the president’s budget proposes cutting its funding by 73 percent.84

The Trump administration has also threatened the bipartisan IIJA. Immediately upon taking office, the administration froze funds for all IIJA programs and cut the staff responsible for carrying them out.85 In addition to creating programs that have helped stimulate the clean energy and clean industry transition, the law made strides toward improving the cybersecurity of the energy grid. A secure and resilient energy sector—especially one powered by clean energy sources—is integral to a clean and secure manufacturing sector. The IIJA instructed the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Office of Cybersecurity, Energy Security, and Emergency Response to provide technical assistance to states and territories in the development and strengthening of their state energy security plans.86 The law also established the State and Local Cybersecurity Grant Program to help defend critical infrastructure. However, the program is set to expire in September 2025, and the Trump administration has already cut staff who manage it.87

The IIJA established the Rural and Municipal Utility Cybersecurity Program, which provided funding to help municipal, electric cooperative, and small investor-owned utilities protect against and recover from cyber threats.88 In addition, the IIJA aimed to bring together the expertise of the DOE National Laboratories and private industry to strengthen the cyber resilience of the nation’s critical infrastructure and energy systems, carried out by establishing the Energy Threat Analysis Center.89 The law also provided funding for the national labs to advance the cybersecurity of distributed energy resources and funded several demonstration projects focused on detecting threats to clean energy infrastructure.90 While it is not clear if each of these programs is directly under threat, the mass exodus of staff across agencies means they will likely be unable to carry out their work as intended.

In addition to cybersecurity rollbacks, the administration’s actions are slowing the United States’ progress on meeting the emissions reduction needed to combat the climate crisis. The manufacturing sector is highly emissive and will be one of the largest hurdles for the United States to meet its climate goals.91 By gutting incentives to clean up the manufacturing sector and canceling projects that were piloting new emission-reducing technologies, the administration’s actions will lead to greater climate and toxic pollution for communities.92

The United States cannot afford to tear down the established systems already defending against known vulnerabilities or to cast away the highly skilled professionals dedicated to this work. Instead, the federal government should be working to build up existing cybersecurity initiatives and encourage coordinated efforts across different agencies and with the private sector. The interconnected nature of the problem—in that disruptions to one company could have cascading effects for others, along with potential national security implications—means that the federal government is best suited to organize, finance, and regulate across the nation.

Recommendations

The federal government should begin by maintaining existing programs and reinstating dissolved programs that support the cybersecurity and decarbonization of the manufacturing sector. It should prioritize keeping cyber-related agencies and programs fully staffed and invest in training more OT and ICS cyber specialists through outreach and apprenticeship programs. It should then enact policies that support the resilience of the U.S. manufacturing sector to both digital and physical threats, with a focus on supporting small- and medium-sized businesses.

In 2024, the President’s National Security Telecommunications Advisory Committee published a draft report that found that many organizations, especially small- and medium-sized businesses, lack sufficient resources for the cybersecurity investments needed to implement best practices. While some of these best practices are relatively easy and inexpensive to implement—such as improving password hygiene and patching known vulnerabilities—others may require significant restructuring of OT systems, with necessary downtime to make improvements.93 The committee suggested introducing new market-based economic incentives, such as tax deductions or federal grants, for commercial organizations that invest in cybersecurity best practices.

For the manufacturing sector in particular, a tax credit or other subsidy could be designed to incentivize upgrades or new projects that employ emissions-reducing technologies and improve cybersecurity resilience. This could be specifically for industries in CISA’s defined critical manufacturing sector for which production is crucial to economic prosperity and national security.94 The Qualifying Advanced Energy Project Credit (48C), expanded under the IRA, is already eligible for industrial or manufacturing facilities implementing projects to reduce GHG emissions by at least 20 percent.95 Projects must meet prevailing wage and registered apprenticeship standards to receive the full value of the credit. Another iteration of 48C could include cyber resilience requirements, harmonized with existing standards in their industries, or make it optional to receive a higher credit. Alternatively, a new tax credit aimed at cyber upgrades could include additional benefits for employing emissions-reducing technologies.

States could also implement tax incentives for companies that both decarbonize and improve their cyber resilience. To make this policy more affordable for states, incentives could be limited to small- and medium-sized entities or critical manufacturing industries. Several states have already implemented tax incentives and grant programs to alleviate the high costs associated with decarbonizing industrial facilities, which could be expanded.

Read more

In addition to the cuts the Trump administration has made to state and local assistance programs, it is working to shift some of the cyber resilience and climate resilience responsibility from the federal government to states and municipalities. A March 2025 executive order from the administration stated that “preparedness is most effectively owned and managed at the State, local, and even individual levels,” in terms of addressing risks from cyberattacks and climate change-fueled extreme weather events.96 This directive inaccurately assumes that states have the capabilities, funding, or even authority to carry out responsibilities handled by the federal government.97 Still, states should do everything in their power to increase support to their critical manufacturing industries.

States and local governments should coordinate to align on the same cyber regulatory requirements and create spaces to share best practices and cybersecurity data between industry and government. Due to the shortage of OT cybersecurity specialists, states should consider pooling their resources to create regional public-private initiatives. These programs could conduct outreach to critical manufacturers that have indicated a lack of resources or staff to properly implement cyber best practices. They may also consider taking on some of the investigative responsibilities of the now-dissolved CSRB and determining what lessons industry can learn from major incidents.98 These regional initiatives could also collaborate or connect companies with the cybersecurity services that already exist for manufacturers, such as CyManII or the Manufacturing Information Sharing and Analysis Center.99

Finally, it is ultimately up to private companies to prioritize preparedness and invest in upgrades that will make them resilient now and in the future. Manufacturers should transition to low-emission production processes and factor in the potential cybersecurity benefits that this modernization presents when implemented strategically. They should view the costs and downtime as necessary investments to avoid far greater costs and consequences in the future. Large manufacturers should consider the cybersecurity of their supply chains and assist the smaller companies they rely on in strengthening their cyber resiliency. They may also connect with or assist their utility companies, particularly if they are in more rural areas where utilities are likely to be understaffed and vulnerable to cyberattacks.100

Conclusion

Whether or not the United States takes action, the urgent need to address climate change, reduce emissions from manufacturing, and protect against the growth of cyber threats will remain. If the United States does not seize this moment and the momentum of a modernizing manufacturing sector accordingly, it will be left behind. If the federal government works to stop this momentum, the United States will be left uncompetitive and increasingly vulnerable. Now is the time to build capabilities and prepare for the unknown vulnerabilities that will continue to emerge in order to reduce the risk of serious impacts in the future.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Lucero Marquez, Shannon Baker-Branstetter, Alia Hidayat, Devon Lespier, and Mike Williams of the Center for American Progress; Nick Merrill of the UC Berkeley Center for Long-Term Cybersecurity; and Harry Krejsa of the Carnegie Mellon Institute for Strategy & Technology for their review of and input on this report. The views expressed in this report are solely attributable to the author.